The human nervous system, comprised of the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves, is responsible for transmitting signals between different parts of the body. Think of this as a complex system of electrical wiring in the body. Breaking it down, our peripheral nerves play a major role in several bodily functions, including movement and sensation.

Just like the rest of our body, our nerves are designed to move. A healthy and happy nerve gets a lot of movement and blood flow. Nerves consume approximately 20% of the body's oxygen supply even though they comprise only about 2% of the body's weight.

Throughout our day our nerves are bending, stretching, and gliding while we perform normal daily activities and movements. It is even normal for nerves to experience some temporary compression with daily activities. Many of us have had our leg "fall asleep" if sitting in an awkward position for an extended period of time. By changing positions or moving around these symptoms go away as blood flow is restored to the nerve.

If a nerve has been compressed or irritated for a prolonged period of time, it can become more of a problem, as unpleasant nerve compression symptoms can become more persistent. This constant nerve compression is often referred to as a “pinched” nerve. It is also known as nerve entrapment, nerve compression, or a trapped nerve.

Prolonged nerve compression or irritation can interfere with our nerves ability to transmit sensory and motor information through the body properly. Symptoms of nerve compression may include:

tingling

burning

numbness

pain

muscle weakness

stinging pain, such as pins and needles

Nerve compression can occur anywhere in the body but most often occurs in the neck, back, shoulder/chest, elbows, and wrists. Nerves can be compressed or irritated by muscle, bone, cartilage, or the intervertebral disks of our neck and back. Inflammation in an area of the body can also affect a nerve’s ability to transmit signals properly.

Commonly diagnosed conditions that involve nerve compression involve sciatica, stenosis, disk herniations, carpal tunnel syndrome, piriformis syndrome, and thoracic outlet syndrome.

Although nerves love movement, an injury that involves a quick stretch or pull to a nerve might damage the tissue surrounding the nerve. As this injured tissue heals, the healing process may affect the nerve’s ability to slide past surrounding tissue and structures, which can also result in nerve compression symptoms.

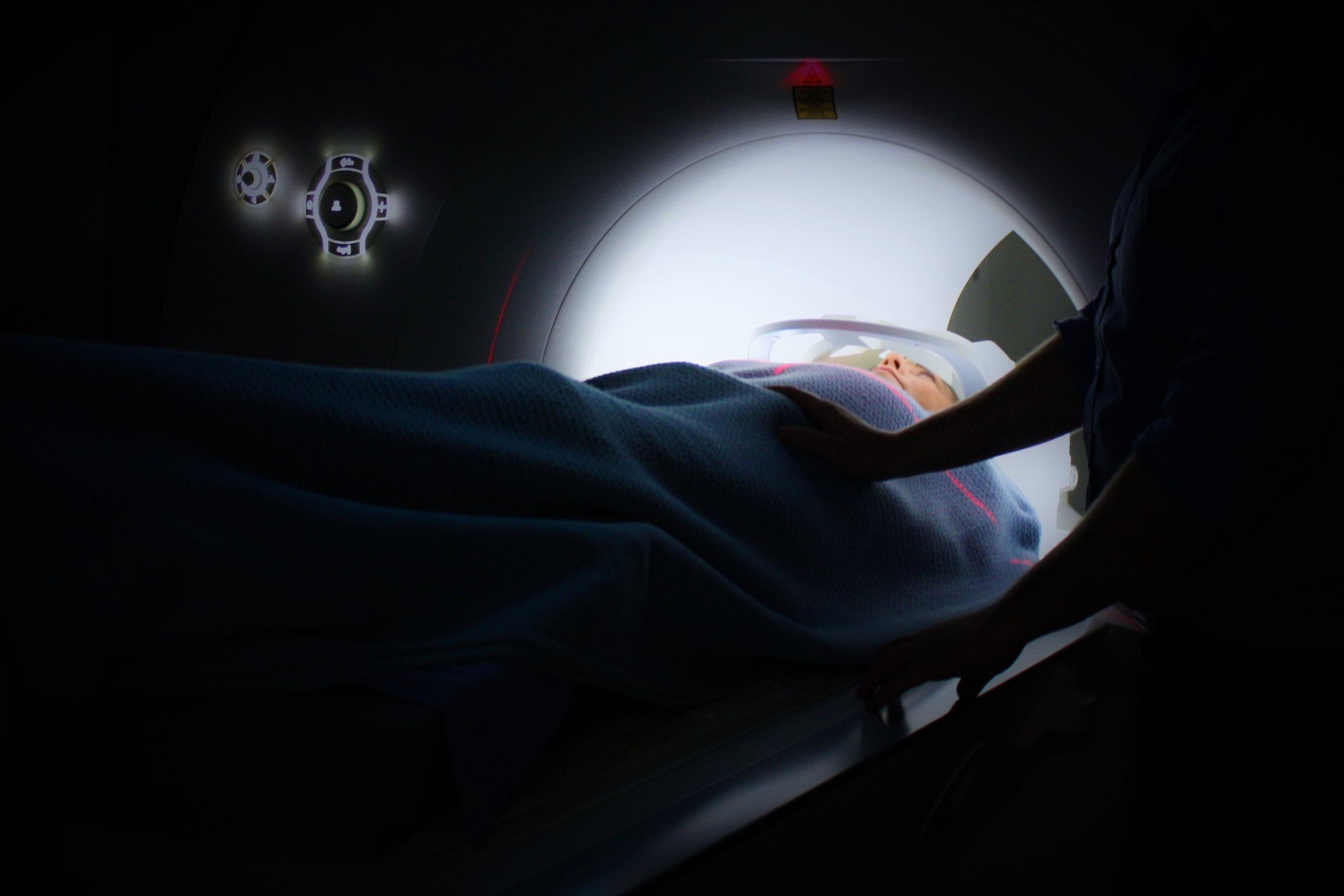

In some cases, medical imaging can help diagnose the source of the nerve irritation. However, a physical therapist can often determine which areas need to be addressed and provide helpful interventions to decrease symptoms without any imaging being done.

Physical therapy can also help to address and improve the nerve symptoms. Physical therapy can improve nerve mobility, increase nerve blood flow, and decrease inflammation of nerves, resulting in decreased symptoms. Exercises can also be used to strengthen muscles that have become weak as a result of prolonged nerve compression. Hands-on techniques by a physical therapist can be used to improve the mobility of the soft tissue around the irritated nerve to help improve its function. A physical therapist can also work to improve postural impairments that may be contributing to nerve compression symptoms.

In conclusion, one of the best ways to keep our nerves happy and healthy is through cardiovascular exercise. Whether it is walking, running, or other sport activities, regular exercise helps nerves stay mobile and improves blood flow to our body and nervous system.